Privity of Contract and Collateral Agreements

- Bryan Wang

- Jun 3, 2020

- 5 min read

The doctrine of privity of contract is an essential feature of Malaysian contract law. Being a creature of English jurisprudence, local application of the doctrine by Malaysian courts heavily rely upon English common law rules and principles.

In short, the privity doctrine stipulates that only parties to an agreement may sue or be sued on it. The doctrine is premised on two other closely related principles in contract law:

(1) Only the 'promisee' (the party who receives a promise) may enforce the promise against

a 'promisor' (the party who makes a promise);

(2) Consideration must move from the promisee to the promisor.

The corollary of this is that third parties who are not privy to a contract may neither sue nor be sued on it. Seems simple enough, doesn't it? Yet the reality of commerce is far from simple. All if not most contractual arrangements are underscored with some layer complexity.

Third party rights and liabilities, for example, often come into play and feature in the background of contractual activity. A bilateral contract, therefore, may not really be just an agreement between two people. A brief discussion on the seminal English case of Shanklin Pier Ltd. v. Detel Products [1951] 2 KB 85 will exemplify this predicament better:

(A) The Case of Shanklin Pier: Overcoming the limits of the Privity Doctrine

The Facts

The Plaintiff (Shanklin Pier) were owners of a jetty on the Isle of Wright, south of England. Shanklin Pier was in discussions with the suppliers of the paint i.e. the Defendant (Detel Products) to have the pier painted by a separate contractor (the Painters). Detel Products assured Shanklin Pier that its paint would last for at least 7 years.

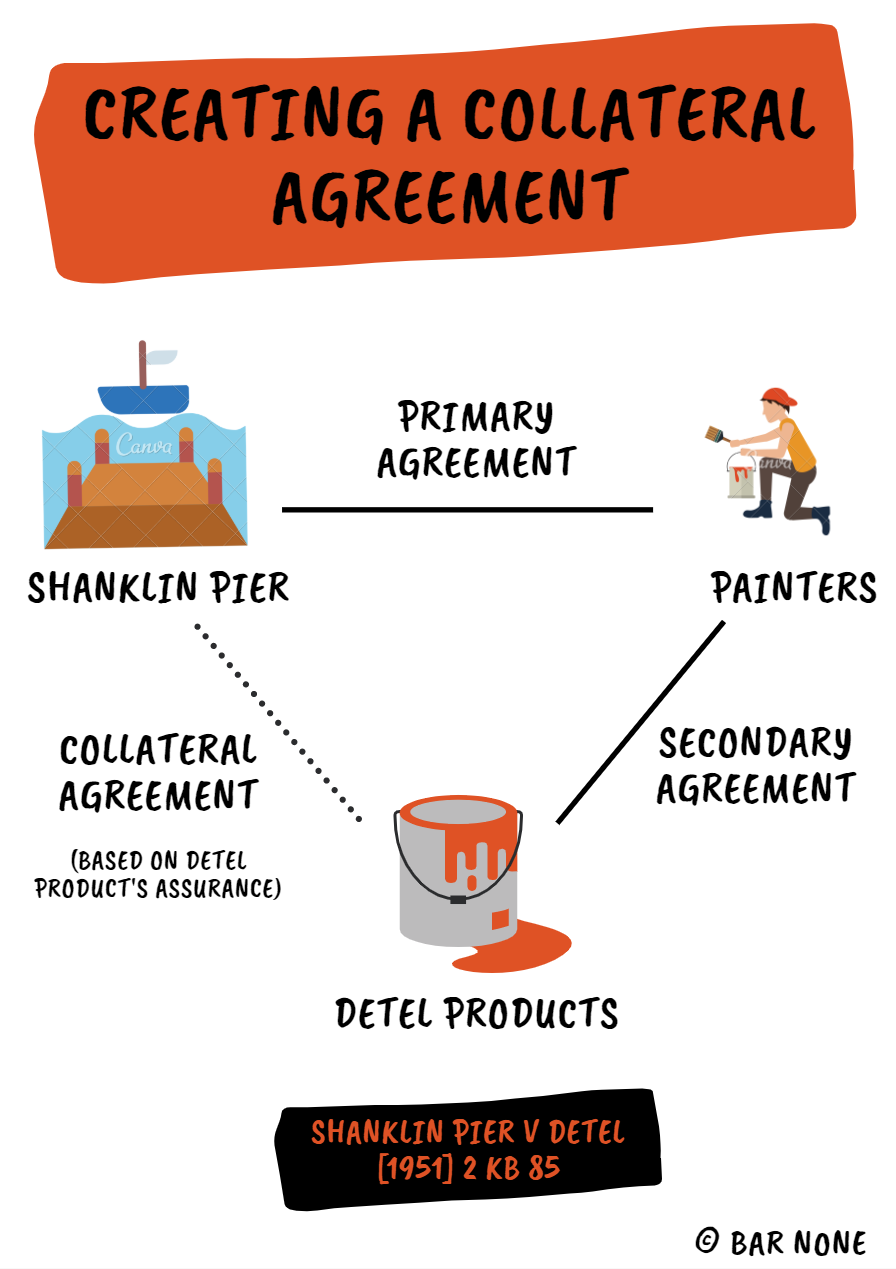

On this assurance, Shanklin Pier entered into an agreement with the Painters to have the pier painted (Primary Agreement), and 'caused' the Painters to enter into a separate agreement with Detel Products for the supply of paint (Secondary Agreement).

As it transpired, the paint supplied by Detel Products did not last very long (a mere 3 months before it began to peel off) and Shanklin Pier then sued Detel Products on this basis.

[Shanklin Pier had exercised its contractual right under the Primary Agreement to determine the type of paint to be supplied, thereby 'causing' the Painters to enter into the Secondary Agreement with Detel Products]

The Problem There was just one problem - the fact that the paint in question was the subject matter of the Secondary Agreement (between Detel Products and the Painters), of which Shanklin Pier was not a party to. Detel Products argued that the doctrine of privity prevented Shanklin Pier from bringing an action for damages on the quality of the paint.

Allowing Detel Products to make us of the privity doctrine as a means to avail itself of liability for misrepresenting the quality of its paint would, therefore, clearly result in an unfair outcome.

The High Court's Decision

The High Court, therefore had the task of preventing an unfair result and overcoming the limits imposed by the privity doctrine without having to disregard its authority. To this end, the High Court created an exception to the doctrine by making the following findings:

Detel Products' assurance to Shanklin Pier in relation to the quality of the paint amounted to a warranty of its quality;

In reliance of this warranty, Shanklin Pier entered into the Primary Agreement with the painters;

In consideration for this warranty, Shanklin Pier 'caused' the Painters to enter into the Secondary Agreement with Detel Products;

The exchange of the warranty in consideration for 'causing' the Secondary Agreement resulted in a Collateral Agreement between Shanklin Pier and Detel Products.

The Collateral Agreement there enabled Shanklin Pier to sue Detel Products for breach of warranty as depicted below:

Through the creation of a Collateral Agreement, Shanklin Pier was able avail itself of an exception to the privity doctrine and recover damages in contract against Detel Products for breach of warranty. The requirements of a collateral contract from the Shanklin case, therefore, may be summarized as follows:

(1) There must be an express statement of assurance amounting to a contractual warranty;

(2) There must be valuable consideration that is given in exchange for this warranty (in the

Shanklin case, this took the form of causing the Painters to enter into the Secondary

Agreement with Detel Products);

Despite being English authority, the Shanklin case has been regularly followed and cited by Malaysian courts. The above requirements for a collateral contract would, therefore, apply locally.

[see for example: Syarikat Imatera Digital Image Services v Dato’ Abdul Nasir Hassan & Ors [2017] 1 LNS 1472; Kinta Sunway Resort Sdn Bhd v Sim Leisure Consultants Sdn Bhd [2017] 1 LNS 566 ; and Bandar Raya Developments Bhd v Ang Yoke Lin Construction Sdn Bhd [1993] 2 CLJ 53]

(B) Other Exceptions to the Privity of Contract Doctrine

Several other exceptions to the privity doctrine exist in common law to mitigate unfair and/or unjust outcomes that may result from strict observance of the said doctrine.

(i) Assignment of Contractual Rights

Where Party A and Party B enter in to an agreement (Main Agreement), and Party B assigns his contractual rights and benefits accruing from the Main Agreement to Party C. Party C may sue on the Main Agreement to enforce said rights and benefits against Party A (as guaranteed under Section 4(3) of the Civil Law Act 1956)

(ii) Agency

Where Party A acts an Agent for Party B, and Party A enters into an agreement with Party C, a contractual relation is formed between Party B (the Principal) and Party C.

This may occur even if Party C is unaware and/or Party A does not disclose that they are acting as an Agent for Party B, otherwise known as the 'undisclosed agent principle'.

(iii) Cheques

Cheques are negotiable instruments prescribed under the Bills of Exchange Act 1949. In short, it is a contract between the Customer and the Bank (Banking Agreement) such that the Customer directs the Bank to pay the amount on the cheque to a Third Party.

The Third Party, though not a party to the Banking Agreement may sue on the cheque to recover the amount stipulated.

(iv) Trusts

Where Party A makes a promise to Party B and in consideration for that promise, Party B promises to confer some/all benefits to Party C.

Given that the benefit of the agreement between Party A and Party B is for Party C, Party A is considered as a Trustee having created a Private Express Trust for the benefit of Party C (Beneficiary). Party A, in their capacity as a Trustee, may therefore sue to enforce Party B's obligations for the benefit of party C (Beneficiary).

If Party A fails to discharge their duty as a Trustee in enforcing Party B's obligations, it remains possible for Party C to sue to enforce said obligations under an Implied Trust.

(v) Insurance Policies

One may also take up a life insurance policy with an Insurance Company (Life Insurance Agreement) for the benefit of another, which effectively create a Resulting Trust in favour of the beneficiaries to the Life Insurance Agreement pursuant to Section 23 of the Civil Law Act 1956. The Beneficiaries, though not privy to the Life Insurance Agreement, may sue upon it s

Similarly, mandatory insurance cover for motor vehicles are premised upon an contract between a Vehicle Owner and an Insurance Company (Motor Insurance Agreement). Though not privy to the Motor Insurance Agreement, Third Parties are able to sue on said agreement to enforce pay outs by virtue of Section 91 of the Road Transport Act 1987.

(C) Concluding Remarks

At some point in time we will need to stop and ask ourselves how many more exceptions should be made to the privity doctrine before it loses authoritative footing and becomes an anachronism. Australian Courts have called for a total rejection of the doctrine, and the UK have reformed the doctrine in its entirety through The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999, yet it remains a feature of Malaysian contract law.

Reform to the scope and application of the doctrine would, therefore, be a welcomed change in hopes of streamlining and clarifying the remit of the general rule of contractual privity with the myriad of common law and statutory exceptions to it.

Comments